Renaissance Masks on the Equator: Exploring the Creole Identity and Tchiloli Theater of São Tomé and Príncipe

By Kwadwo Afrifa – November 28, 2025 13:00

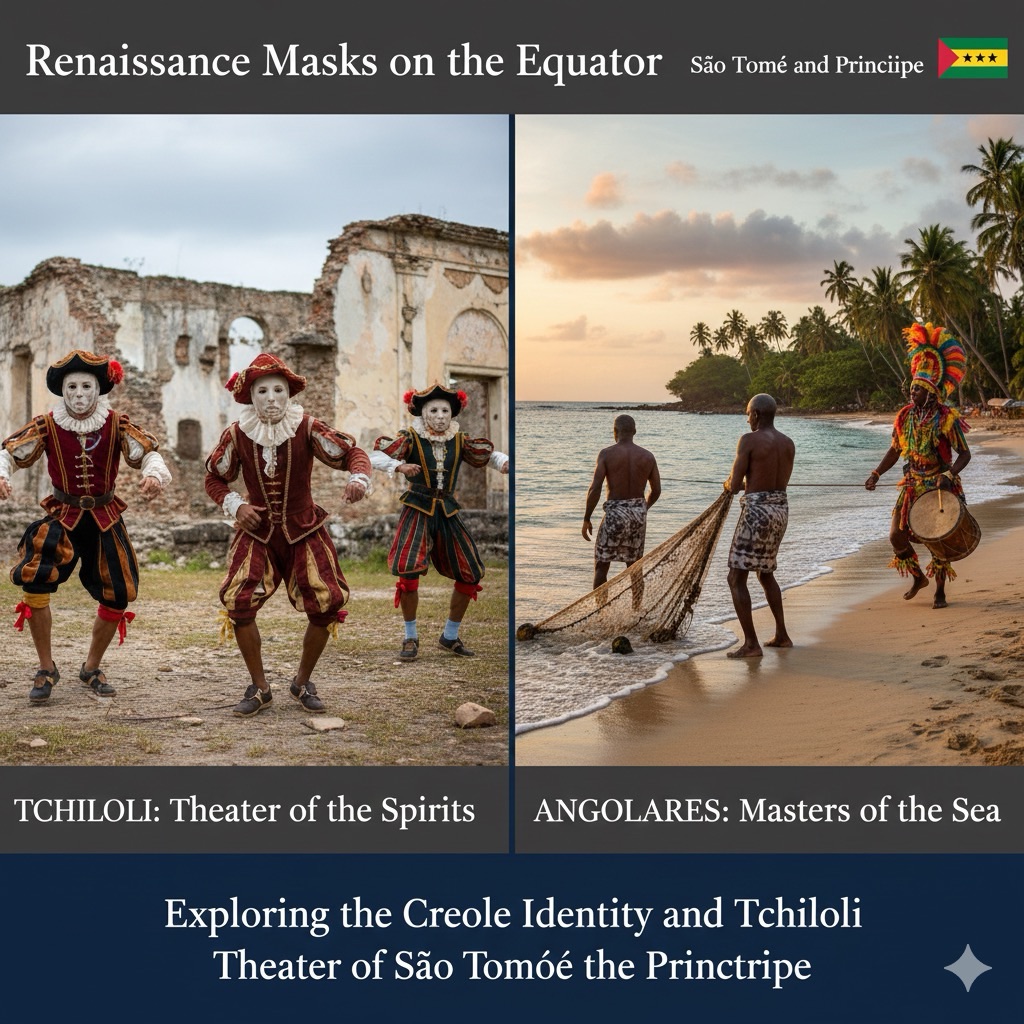

This image vividly showcases the unique cultural tapestry of São Tomé and Príncipe. On the left, masked performers in elaborate period costumes, set against a backdrop of decaying colonial architecture, embody the surreal ‘Tchiloli: Theater of the Spirits,’ a centuries-old Renaissance tragedy reimagined. On the right, Angolares fishermen haul nets from the ocean, representing their heritage as ‘Masters of the Sea,’ with a vibrantly dressed Danço-Congo performer in the background, hinting at their rich maritime and celebratory traditions.

Titled ‘Renaissance Masks on the Equator | São Tomé and Príncipe,’ this visual encapsulates the article’s exploration of ‘the Creole Identity and Tchiloli Theater of São Tomé and Príncipe,’ highlighting the islands’ profound cultural fusion.

Our expansive journey through Africa’s diverse cultures now lands on the volcanic archipelago of São Tomé and Príncipe. Floating in the Gulf of Guinea right on the equator, this small island nation offers a cultural experience unlike any other on the continent. Uninhabited until the arrival of the Portuguese in the late 15th century, the islands became a crucible where African and European traditions melded in isolation to create a distinct Luso-African Creole culture. Here, we delve into the fascinating world of the Forros, the Angolares, and the surreal, centuries-old theater tradition known as Tchiloli.

The culture of São Tomé and Príncipe is rooted in the history of sugar and cocoa plantations (roças), which brought together enslaved peoples from the Kingdom of Kongo, Benin, and Angola, and later contract laborers from Cape Verde. This convergence created a highly stratified but vibrant society with unique linguistic and artistic expressions.

Tchiloli: A Renaissance Tragedy Reimagined

The most singular cultural treasure of São Tomé is Tchiloli (or the “Tragedy of the Marquis of Mantua”). It is perhaps the world’s most unique example of cultural syncretism.

* The Story: The play is based on a 16th-century text by the Madeiran poet Baltasar Dias. It tells a complex story of the Emperor Charlemagne’s court, involving a murder, a trial, and a debate on the rule of law versus imperial power.

* The Performance: While the text remains faithful to the Renaissance original, the performance is entirely African. The play acts as a form of ritual, often lasting five to six hours.

* Visual Surrealism: The actors wear anachronistic costumes that are a visual feast: European velvet capes and crowns mixed with modern symbols of power like sunglasses, gloves, and even mock telephones or typewriters used during the “trial.” They wear small, pale mesh masks that give them a ghostly, static expression, contrasting with their energetic dance movements. It is a profound community event where centuries-old questions of justice are re-enacted for a modern audience (Seibert, 2009).

The Angolares: Survivors of the South

While the majority of the population are Forros (descendants of the first unions between settlers and enslaved people), a distinct and historically isolated community exists: the Angolares.

* Legend of the Shipwreck: Tradition holds that the Angolares are descendants of enslaved Angolans who survived a shipwreck in the mid-16th century. They established an independent community in the rugged, isolated south of São Tomé Island, resisting Portuguese control for centuries.

* Culture of the Sea: The Angolares are renowned fishermen and boat builders. Their isolation allowed them to preserve a distinct language (Angolar) and cultural identity separate from the Forros.

* Danço-Congo: Closely associated with the Angolares (and the Tchiloli tradition) is the Danço-Congo (or Captain of Congo). This is a frantic, pantomimic dance performance involving vibrantly dressed dancers, drummers, and a central “captain.” It is a boisterous, often humorous, display of resistance and African heritage, contrasting with the solemn legalism of Tchiloli.

Life on the Roça: A Plantation Legacy

The cultural landscape is also physically defined by the roças (plantations). For centuries, these self-contained estates were the centers of life, creating specific social hierarchies and interactions between the Forros, the plantation owners, and the serviçais (contract laborers, often from Cape Verde or Mozambique).

* Architectural Heritage: Today, the crumbling colonial architecture of the roças, reclaimed by the lush rainforest, serves as a backdrop for daily life and cultural festivals.

* Culinary Fusion: The cuisine reflects this mix, blending Portuguese ingredients with African staples like breadfruit, matabala (taro), and intense tropical spices, exemplified in dishes like Calulu (a dried smoked fish or chicken stew).

A Microcosm of Convergence

São Tomé and Príncipe is a living laboratory of creolization. In this small archipelago, a Renaissance play about Charlemagne becomes a uniquely African ritual of justice, and a community born of a shipwreck maintains a proud legacy of independence. It is a testament to the human capacity to create new, vibrant identities in even the most isolated environments.

Our next article will return to the mainland, taking us to Senegal, where we will explore the traditions of the Wolof people, known for their influential Griot caste and Teranga (hospitality), and the Serer people, with their ancient spiritual connection to the land.

References:

* Burness, D. (2005). Ossobo: Essays on the Literature of São Tomé and Príncipe. Africa World Press.

* Seibert, G. (2006). Comrades, Clients and Cousins: Colonialism, Socialism and Democratization in São Tomé and Príncipe. Brill.

* Shaw, C. (1996). “Oral Literature and Popular Culture in São Tomé and Príncipe.” The Post-Colonial Literature of Lusophone Africa, pp. 248-273.